It has been fantastic to stumble across painters with similar intent, using destruction and repair as processes of creation, but with different forms of expression, from Berlin to Argentina. I have really enjoyed looking and writing about other artists' work. Putting my thoughts down in black and white somehow helps me to articulate them more clearly to myself, encouraging me to research rather than assume a superficial understanding. I want to keep this up: the first habit which I hope has stuck.

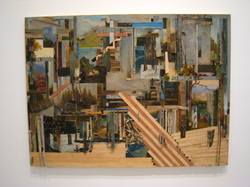

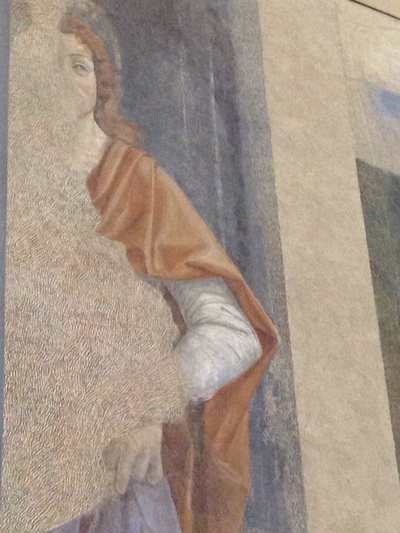

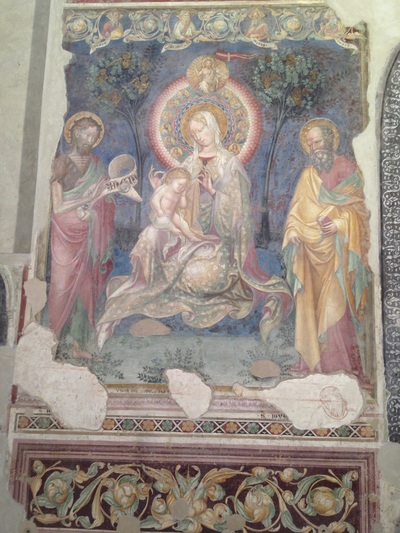

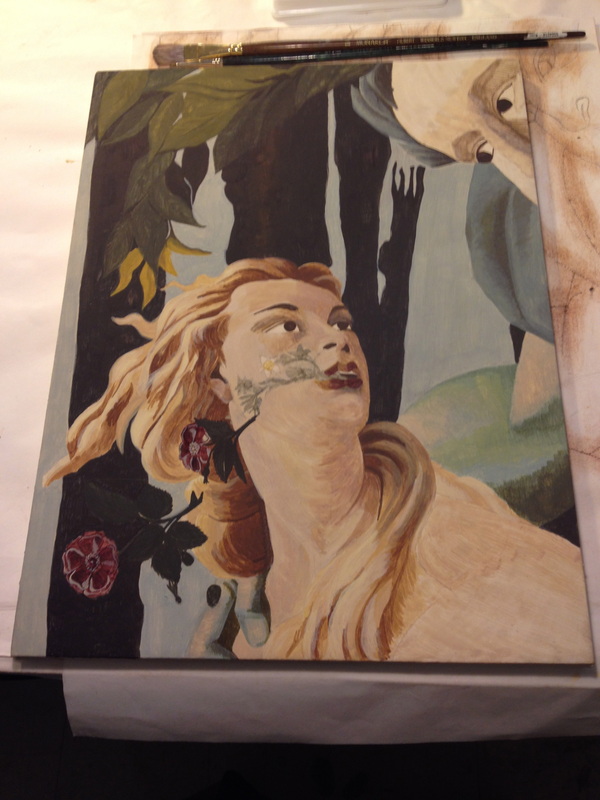

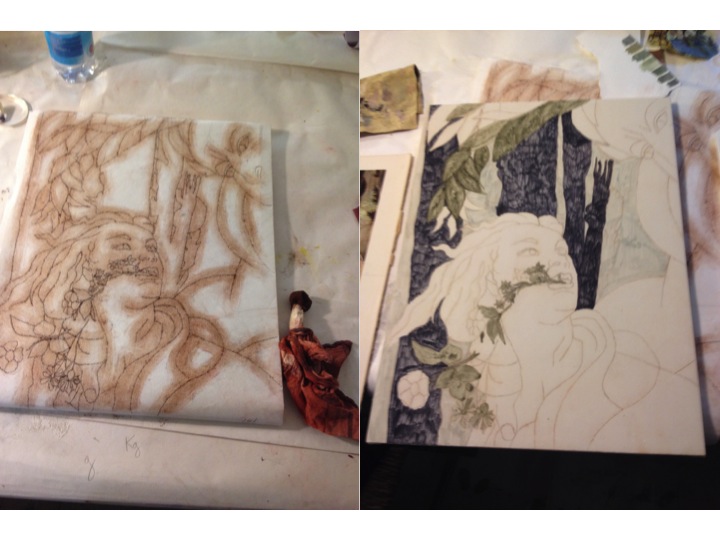

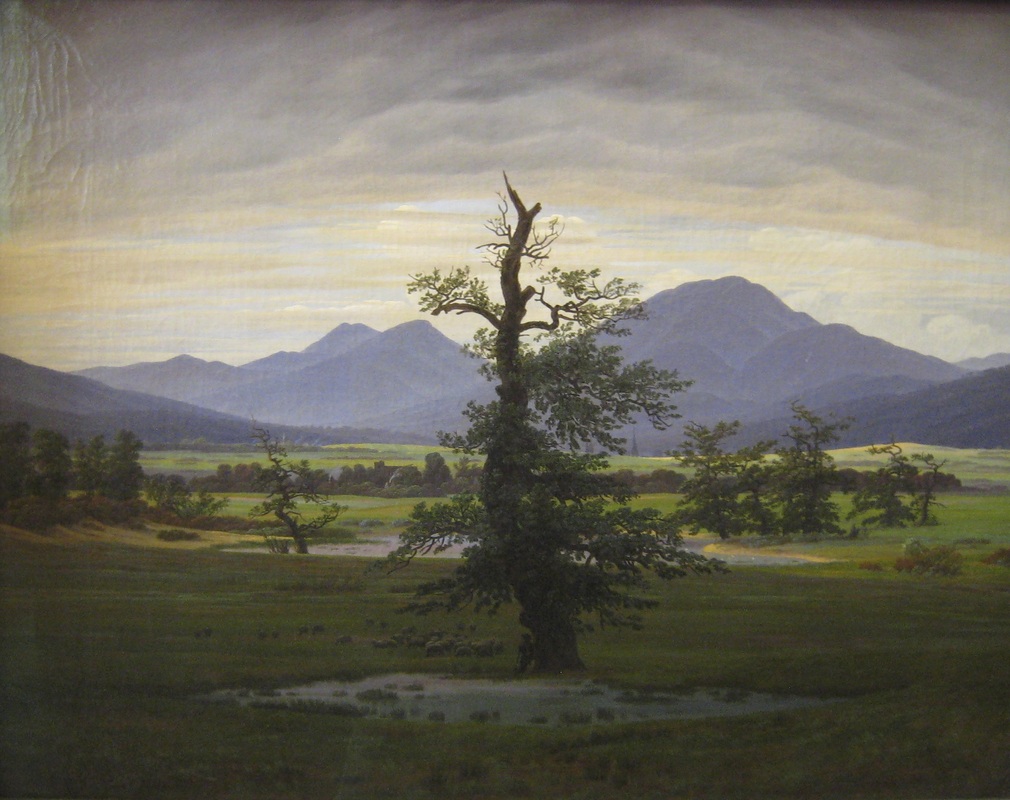

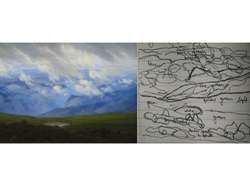

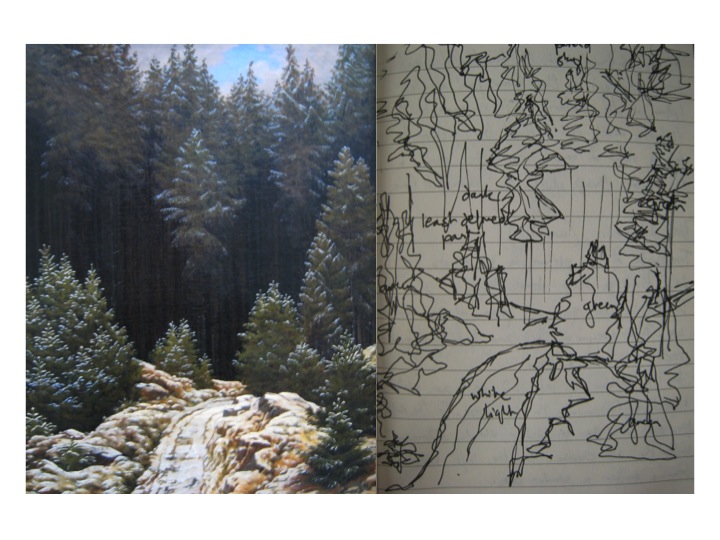

I started this blog thinking it would be about exploring materiality, the simplicity of the canvas warp and weft. Instead it has become clear to me that my work is about subverting the traditional role of painting as a window on the world. Using landscape, that rather cliched romantic genre, to present a recognisable image and then subverting or disrupting it through collage and re-sewing. The latter, a feminine, deliberate, methodical way of expression, and of destruction, and of repair. I know that my interlude in Italy into copying a section of Botticelli's Primavera was confusing; but trust me, it was about learning the technique of painting in tempera not an about turn, style-wise.

Over the past few weeks I have literally sweated over re-sewing a piece: a drawing of nettles made in Berlin which I abstracted with purple threads. It generated a lot of intrigue as I worked on it in hostels and on bus journeys. But somehow at Ezeiza airport on the way home I lost it and all I have left is a photo of the original untouched drawing, memories and lost hours. Perhaps making art and being transitory aren't such a good mix after all, at least not for someone as careless as I can be. This certainly wasn't the injection of art into real life I had in mind when I rambled back in September about how exciting it would be to present art somewhere unexpected.

Which brings me very neatly to introducing the next Reside artist: Claudia Boese! Having developed the language of abstraction within her painting, Claudia would like to move towards a figuration of ideas. Her studio in a church tower in Ipswich and a new allotment may serve as inspiration. But perhaps it's best if I leave Claudia to explain things in her own words. I look forward to seeing where Reside takes her over the next six months.

So, all there is left is for me to say goodbye. Thank you Michaela for choosing me and giving me this experience. And to everyone who has read, commented and retweeted my blogs. The immediate reaction, feedback on how my work is developing, has been so valuable to me. I leave you in the hands of Claudia, and with the one word which has been common to everywhere I have been over the past six months: Ciao!

RSS Feed

RSS Feed