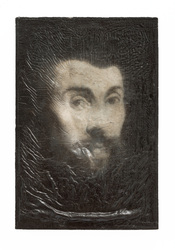

And what destruction! The paintings are gouged, pierced, flecked, scratched, scrunched, shrouded and pummeled. The act of their destruction being all the more perverse because it is carried out on paintings which have been carefully rendered with art historical references and technique. I imagine the artist labouriously painting for weeks or maybe months, building up layer upon layer of paint, and then one day turning around and destroying these creations in which he has invested so much. The gallery’s press release states that Samorì examines obsession, one aspect of which is the obsession of the artist with his own work. Yet he is neither an artist who is precious about his paintings, nor a Victor Frankenstein, who seeks to destroy because he is horrified by what he has created. Far from it, he then puts his destroyed masterpieces on display. His paintings both refer to the past through their subject matter and the manner in which they are depicted, and are rooted in the contemporary, by their very recent act of destruction.

I was first drawn to Vomere, a copper-surfaced diptych, peppered by oval forms, the heads of an audience who are looking at a painted figure forming a table in front of them. This life-size figure is in the process of being physically dissected, a process we may have interrupted. The skin of paint has been half pushed and pulled away, echoing the fragile surface covering our bodies. But rather than revealing bones, muscles and tendons, we see a black and blank undersurface. Pulling the surface away hides rather than enlightens and we, like the unseen copper-covered faces of the curious in the diptych, are left un-seeing.

It may seem strange to link these painters together as their work references very different eras and, so, outwardly appears entirely distinct. However, I think they have commonalities in their underlying intent, and in the use of destruction as part of their creative process. By grounding his work in a more distant art historical past, Samorì displays a technical virtuoso that the other artists do not. For me, this adds a rich drama to his work and makes the final act of destruction all the more powerful.

Guarigione Dell’Ossesso by Nicola Samorì is at Galerie Christian Ehrentraut, Berlin, from 25 October to 7 December. With thanks to the gallery for providing me with photographs from the exhibition to use in this blog.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed