His work is easily identifiable, as popular images used to represent the Romantic era. But my observation, as I have sat in museums and sketched or written, is that people don’t spend very long looking at them once they have linked image and artist. This may be because many people don’t actually spend very long looking at any art, but perhaps it is also because his paintings are too earnest and sentimental for our contemporary eyes, the colours, particularly of sunrise and sunset, now too clichéd and cloying. Looking past the vivid orange sky and contrasting lilac mountains I have found these seemingly straightforward paintings are created from complex compositions and unusual perspectives which hide as much as they reveal.

I feel that they really play with me, as a viewer. In some cases frustrating my view, hiding as much as they reveal. Rocks rise up in the centre of the picture, as in Das Kreuz im Gebirge, The effects of light or weather are employed to obscure the view. The landscapes of Ziehende Wolken, above, and Nebel im Elbtal are partially shrouded in mist, with the viewer receiving only fleeting glimpses of the valley below in the latter painting. In some pictures the foreground is cast into gloom making it difficult to discern any detail. With this latter obstructing effect, however, I am unclear whether Friedrich intended it to act as strongly as it does or whether it is the combined effect of the museum lighting, glazing and darkening varnish on the works.

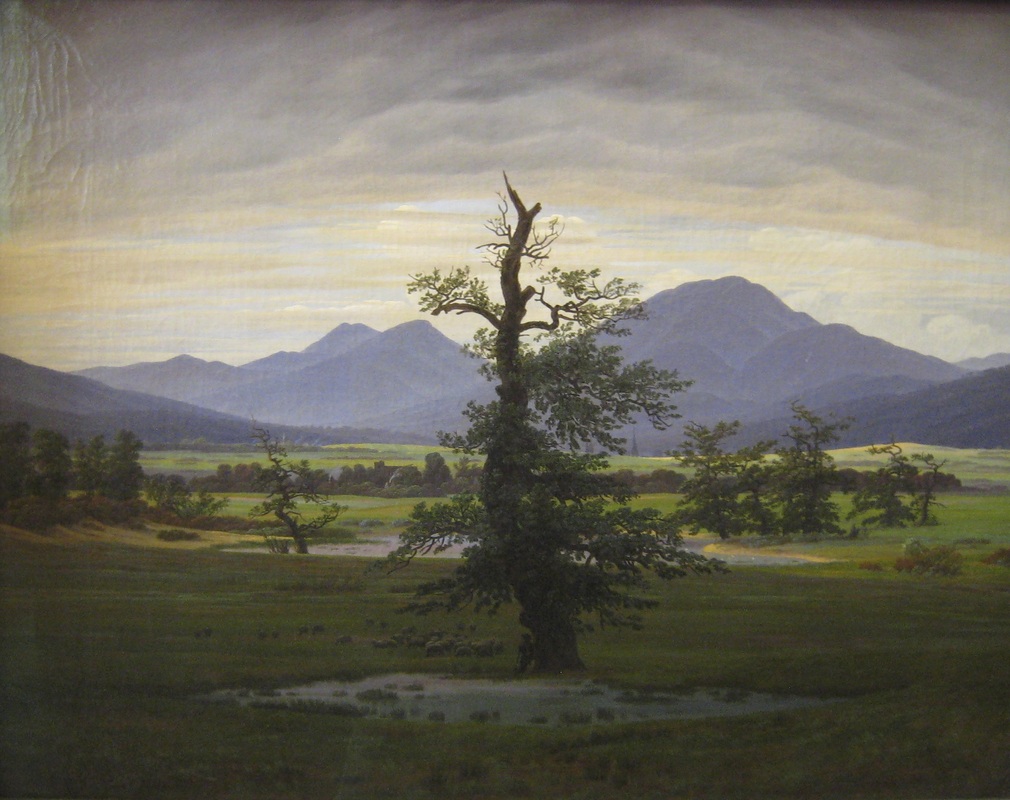

The composition directs the way in which we navigate through the elements of the painting. A path or river directing the way in which we move from fore to mid to background. Strong vertical, horizontal or diagonals attracting our attention at the expense of small details such as the shepherd tending his flock in Der einsame Baum, as I mentioned before (above), or a sailing boat about to ground itself in the shallow river in Das Grosse Gehege bei Dresden. These details only revealed themselves to me as I stopped and really contemplated the pictures.

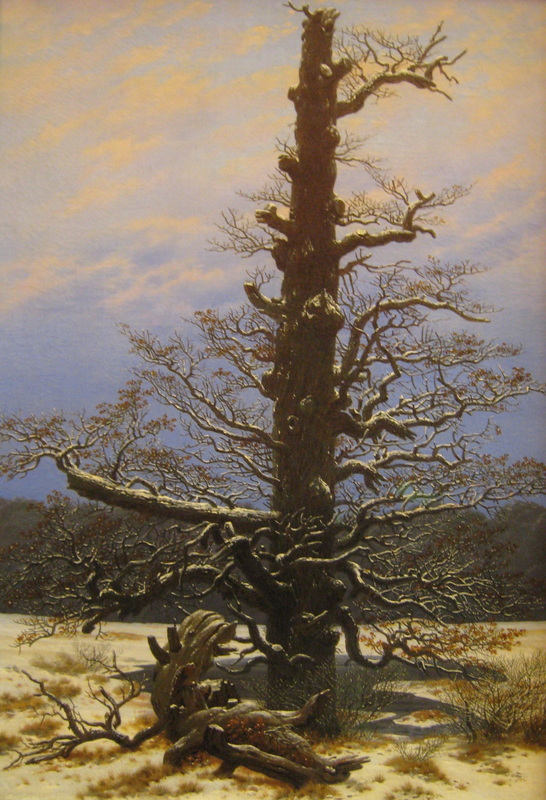

Friedrich also used changes in perspective to direct attention to particular elements of the composition. In some cases the picture is uniformly detailed, performing a feat the eye cannot manage, of presenting the background to the same level of detail as the foreground, flattening away pictorial illusion. A picture such as Eichbaum im Schnee, below, focuses on a single tree, obscuring anything but the foreground. While the composition and detail of Wiesen bei Greifswald focuses on the background of the town of Greifswald, with the foreground of bushes and mid-ground of horses and geese in a meadow, seemingly incidental, decorative elements for the main image. Copses or rock formations serve as formal markers between fore, mid and background, setting the scene out as though in a theatre-set stage.

[1] The Abstract Sublime, Robert Rosenblum, Arts News, February 1961

RSS Feed

RSS Feed